by Laura Lee

Director of Outreach and Development, Cuyamungue Institute. Copyright 2016

The Masked Trance Dance has a surprisingly long history. Go looking for it, and you find it clearly writ on our oldest surviving “tablets” — cave walls — in the records left by our first artists, in our earliest cultures.

Among the most famous images from Europe’s painted caves, notable for the rarity of human figures, we find three fine example of Masked Dancers.

They wear the head, horns, and tail of bison and reindeer. They stand upright on human legs and feet, one leg raised mid-way in a half-step. That is not a bow the bison-headed figure holds, but is thought to be a nose flute, popular in some cultures today. The horns make quite the impressive headdress, the skins a ready cape, one that leaves the legs free for dancing. These figures look to me like ancient “snapshots” of shamans in a Masked Trance Dance!

Above Left: Two shaman dancing in the Trois-Freres Cave, Dordogne, France.

Left: Bison-masked shaman has one arm extended and one leg lifted.

Right: Shaman with Deer Mask and Antlers gazes at the viewer while leaning forward with hands together.

Far Right: Les Sorcier”/“The Sorcerer” Engraving on wall of Gabillou Cave in Sourzac, Dordogne, France is over 22,000 years old, from the Solutrean or Early Magdalenian culture. A little over a foot tall, it is located at the narrow end of the cave, allowing entry by only a few people at a time.

Note: These two figures, both known as “Les Sorciers” or “sorcerers” are found in the Trois-Freres Cave, but not in the same chamber. I’ve put them side by side here for comparison. In this discussion I am using the term “shaman” to describe the figures, a term more in tune with the indigenous cultures of Ice Age Europe. The term “sorcerer” hails from a much later era, and our Western culture, which has a markedly different understanding of “magic”.

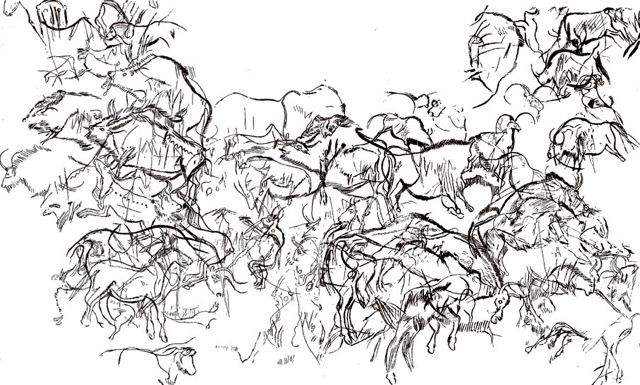

Above: Right hand wall of the Sanctuary Chamber of Trois-Freres Cave. Note the location of the Bison-Headed Shaman to the left of center, surrounded by dozens of predominantly horse, bison, and sheep, superimposed one atop the other.

There is yet more to read in the larger cave wall on which the Bison-headed shaman is engraved. Taken as a whole, we have one wall of a small remote room covered with overlapping engraved drawings of predominantly reindeer, bison, horse surrounding the shaman. It’s known as the “Sanctuary”. The shaman figure is dated among the oldest in the chamber, at 13,000 years old, and 13 feet above the cave floor. The last of the surrounding 280 engravings of animals took up to an additional thousand years to complete. They are layered one over the other, but for the shaman who stands alone in a triangular clearing.

Do you believe in “sympathetic magic”? This is the standard explanation for this scene — as a depiction of a shaman performing a ritual to “call” the prey to the hunters, while artists fulfill this through representation, drawing herds upon herds, an abundance of all types of prey. This would be “praying for prey” in the hope that visualizing the goal in a concrete way, drawing pictures, can influence, in a cause and effect way, the chance of it actually happening. Did our ancestors believe that drawing the prey on a cave wall would actually help draw the prey to the hunters? I could more easily believe, if such a scene was related to the hunt, it was more as a staging for a rally of enthusiasm and building team coherence before embarking on such a dangerous enterprise.

Actually, I see this scene very differently, not as a hunt, but as a celebration. I see a shaman dancing is the midst of the animal spirits, just as I have done in many a spirit journey, and many a Masked Trance Dance at the Cuyamungue Institute over the last twenty years. I see a shaman dressed as a bison, because he is aligned with the Bison Spirit, it’s his or his family’s animal totem, or the spirit that has called him. He is dancing, perhaps as part of the ritual that induces that altered state of consciousness that supports a spirit journey, a practice that continues today in many parts of the world. Or equally possible, this scene represents him inside his spirit journey, dancing with the bison and horses, in a celebration and coming together of kinship, of the shared journey of life. Or perhaps both. It is the clever artist who speaks volumes in multiple layers of meaning. These artists were intent on, and adept at, conveying the merging of ordinary reality with the alternate reality of spirit. I read, in this “page” of the cave, the telling of a spirit journey that I recognize as similar to one from my own journal (minus wearing the buffalo headdress and robes) that could nicely fit this illustration:

“I look around to see I am on a broad plain under a clear sky. Horses appear. They come up to me and nudge me in greeting. They know me. They take me into the herd and crowd around me, I as excited to meet them as they are me. Herds from all sides run up to join in. They are gesturing me to dance, as young sleek colts leap and kick up their heels for the sheer joy of it. More horses, more hooves stamp and stomp, a thundering chanting beat as more animals of the surrounding hills join us, animals as far as I can see. We dance with joy, for the wind and sun and earth and rain, a wild dance of exuberance, for the joy of being alive, to reach out to the universe with thanks, our dance is the applause.”

Some traditions use dance to enter into the trance, but the CI tradition is to stand in a posture as recorded in ancient art. With what body do I dance in a spirit journey? I am standing still, yet my spirit body, my energy body, this body that has not physical dimension but is palpable all the same, I am dancing. With what eyes do I see the animal spirits around me, dancing? With what ears do I hear more than the rattle Paul is shaking? Another set of senses, my inner, spirit senses, have lit up to take me into that other dimension. And what pent up part of my soul finds flight, release, solace, sanctuary, acceptance into some higher level, while dancing with the spirits? What part of me recognizes this as home, a place familiar? Where the slightest nudge sends me back to rejoin my ancestors, in the “eternal now of the alternate reality,” as Dr. Goodman put it.

She advertised the spirit journey as a form of “psychological archeology” in which we could experience the world as our ancestors had. And so its quite easy for me to believe that this is the type of experience that is writ large on that cave wall, if we can decode it. If it was indeed a sanctuary for the artists and shamans to take flight with the spirits, just as we do today in the kiva at CI.

I would sooner believe that, than to adhere to one of the common interpretations of the bison-headed figure “as some kind of great spirit or master of animals.” Really? The human figure is very small compared to the size of the animals surrounding it. And doesn’t use of the term “Master” seem born of today’s hubris, and not theirs? For that’s not what I see when I try on the worldview of those early cultures. Humankind had not yet mastered anything! The Ice Age was a challenging climate, large scale predators made for a hostile environment, and our stone and bone tool kit was in its first stages. I have great admiration for the inventive, creative minds of our ancestors, and for their survival strategies — a key one being to tune in to, and work with, Nature. Well, of course; that’s all they knew. Further evidence of the close relationship of mutual respect with the animals who shared their world is reflected in how accurately and beautifully they were drawn on those cave walls. Animals were the featured stars of the show, making up the vast majority of images. The human or anthropomorphic figure is rare. Sightings of animals in the wild, and of natural spaces left untouched, still leaves us breathless. I believe our ancestors were just as enchanted, and deeply moved, by the sheer beauty and majesty of the natural world as we are today. And in indigenous stories brought forward through time, the animals are still spirit beings, teachers, and equals — brothers and sisters on the web of life.

As a young species, only 250,000 years old, the vast majority of our timeline has been spent living the indigenous way. What changed? Our climate, for a start. The Ice Age ended. Our modern way of life, and the worldview that followed, was paved by agriculture, possible only in the last ten thousand years, in this latest of the all-too-brief 13,000 year warming cycles that have been clocked in the geologic record, sandwiched between Ice Ages lasting on average a hundred thousand years. It’s been a very recent development for we humans to “conquer” Nature and devise technology to circumvent her checks and balances, as we can today in every aspect of our material culture and Age of Science. We moderns paved the way for a new hierarchy, with humans at the top of the heap, by downgrading animals. Recasting them as pets, beasts of burden, factory-farm commodity, giving mythical devils horns and hoofs, all has pushed them from our core, to leave center stage for we humans. We now elevate ourselves above all else. The animal spirits may still try to speak to us, but we have D-listed them to the talking animals of children’s fairy tales and Saturday morning cartoons.

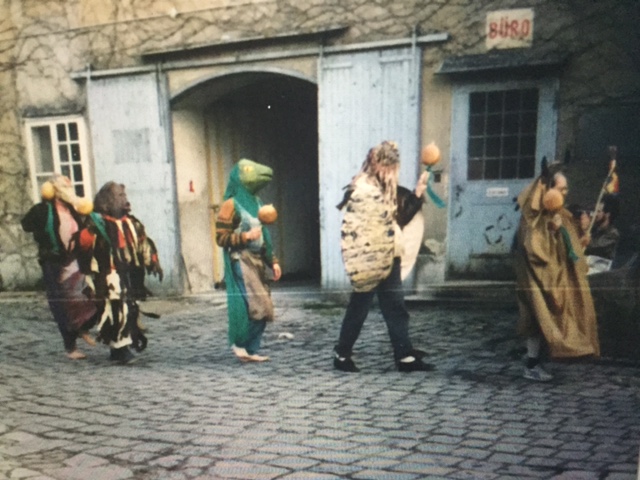

Dr. Goodman gave us one remarkable way to reach out to those ancestors, all of ancestors and commune with the same spirits they did. And she handed her Institute its own Masked Trance Dance tradition, inspired in 1981 by a young man named Franz who invited her to the Buddhist Center of Scheibbs, Austria to conduct the first such exercise inspired by the local custom of enacting a rite of Nature with animal costumes. It was a long tradition of Masked Trance Dancing, which Dr. Goodman revived by giving it a new/old, trance procedure. We can look around to see it was once a very wide spread tradition.

Internationally acclaimed artist George Rivera, former Governor of the Pojoaque Pueblo, and long-time friend of Dr. Goodman, created the magnificent sculpture of a buffalo dancer wearing a buffalo headdress that greets visitors to the Buffalo Thunder Resort. Watching Buffalo Dancers in action in colorful regalia at an annual pueblo dance, is to witness, to sense the spirits come forth, bringing power and blessings.

I saw the universal reach of the masked trance dance on an island off the coast of Australia, in the Northern Territory where the Arafura Sea joins the Timor Sea. Paul and I were on a tour of the Australian Outback with Graeme and Shelley Woodrow. Having an extra day in the coastal city of Darwin, we took a two-hour cruise over to Tiwi islands, ancestral and exclusive home of the Aboriginal Tiwi tribe. Upon landing, our small group was welcomed by an elder of the cultural center and museum, who walked us over to a ceremonial site. We took our seats in a circle around a fire pit as introductions were made. An armful of green leaves still on the branch — their traditional smudge — was thrown on the fire, and as we stepped forward to stand in a circle as one elder used a leafy branch to wave the billowing white smoke over us for ritual cleansing. Then he introduced the dancers, local tribesman and women. One by one, they stepped forward to perform a minute or two of their particular dance steps, to the sound of chanting, stomping of feet and staccato beat of one set of resonant wooden clapping sticks and many hands. As each finished his step with a flourish, we were asked to guess the animal represented. Each family group had an animal totem, gave that family their identity, their steps to the dance. And with an economy of form and gesture — hands and arms held momentarily in arrested motion, a leg raised and angled just so, head cocked with wide-eyed stare — crocodile, buffalo, turtle and shark spirits emerged briefly though clearly. True, we were just getting the merest, for-the-tourists glimpse of their traditions. Still, I could readily imagine the power generated by a  full-fledged, community-wide dance in full regalia, one that went the whole night through. And so could a recent group from British Columbia, they told us, a delegation of Native Americans who had wept with them to find so much shared tradition among two nations separated by half a world.

full-fledged, community-wide dance in full regalia, one that went the whole night through. And so could a recent group from British Columbia, they told us, a delegation of Native Americans who had wept with them to find so much shared tradition among two nations separated by half a world.

The Tiwi had painted their faces and limbs with yellow and white ochre, in bold stripes, curving lines, and dots. I only then realized how simple a mask could be, that with the simple abstract patterns, all similar yet unique, they were both masked, and robed. They wore the marks of their family’s totem animal, that was its garb, which prepared them to enter into that space shared by the spirits. I had just witnessed a modern day Masked Trance Dance, one brought forward through time by this most ancient culture that can confidently trace its roots back the 60,000 years to their first steps onto the shores of Australia.

Sixty thousand years! That is twice and three times the age of the cultures that painted those caves in France and Spain. Calculated at five generations per century, that is 12,000 cycles in which Aboriginal elders passed their traditions down the line. In my mind’s eye I saw them all crowd around us, spiraling around and around in a long line, filling the ceremonial circle. My European Ice Age ancestors, too, found passage between the worlds once again, leaping from their cave walls, joining the dance, and nudging us along. I first came to the Cuyamungue Institute over twenty years ago, seeking a connection with my own indigenous ancestors. I found much, much more than that. I found that I can dance equally well in this reality, or the alternate reality. I found there is much to dance for, and with. And I picked up my long-lost ancestral ties, and knit them back into the web of life.

At the next Masked Trance Dance at CI, Paul and I will be dancing in celebration. I hope you’ll join us.

About the Author:

Laura Lee first met Dr. Goodman over the phone in an interview for her nationally syndicated radio show – a show she hosted for more than a decade. “I was immediately taken with the idea of ‘psychological archaeology’, as Dr. Goodman put it, and experiencing the worldview of our ancestors from the inside out. I also felt comfortable with this work not being a human construct or dogma or belief system, all of which I held suspect. Rather, here was the rediscovery of an innate ability to throw open the doors of perception on the level of the physiology, something the body/mind already knew how to do and only needed activation of the ‘ON’ switch.”

“I value the purity and self-empowerment of that. Felicitas then sent me a little booklet that explained how to do this on my own. I had an experience that demonstrated without question that this was real, that here was a way to continue, safely, easily, and ‘on demand’, the spontaneous such moments I’d had since childhood. Soon Paul and I were heading to Santa Fe for workshops at the Institute, and further interview with Felicitas. I felt I’d come home! And now I’m happy to be involved with the outreach effort to bring this, universal a method as it is, to all who resonate with this.”