Darrin Lowery, a coastal geologist, has made 93 scientific visits to Parsons Island in the Chesapeake Bay, where he and his team have uncovered 286 artifacts from the earliest days of humanity’s settlement in North America. The oldest of these items was embedded in charcoal that dates back 22,000 years — 7,000 years earlier than humans were previously thought to have been in America.

Lowery’s research was backed up by similar finds in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park, which seemed to insinuate human settlement between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. And if Lowery’s findings are accurate, these discoveries could rewrite American prehistory as we know it.

modern scientists mostly agree that humans inhabited the Americas as early as 15,000 years ago. But over the course of the past decade, Lowery and a group of cohorts have made frequent trips to Maryland’s Parsons Island, which is rapidly eroding as sea levels rise.

This rapid erosion means researchers have limited time to find artifacts on the island, but it’s also part of the reason researchers are so fascinated with the area in the first place.

In 2010, Lowery published an article in Quaternary Science Reviews in which he described layers of windblown silt deposited at Maryland’s Miles Point between 13,000 and 41,000 years ago — but Lowery lamented the “unconformity” of the sediment layers. Thousands of years of history, he said, were missing.

That’s when Lowery discovered a black streak of sediment coming from Parsons Island, which he believed could fill in those missing years. With the permission of the Corckran family, who owns the 78-acre Parsons Island, Lowery began his research, hoping to unveil a complete geological timeline from Parsons Island’s sediment.

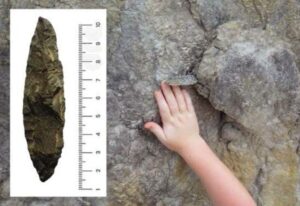

Then, in 2013, he made an even more stunning discovery. Embedded in a crumbling wall, Lowery and his team found a leaf-shaped prehistoric stone tool. After dating the surrounding sediment, they realized that it was more than 20,000 years old.

Of course, 20,000 years ago, this area wasn’t a coastline at all. Much of the region would have been covered in a sheet of ice, with the tools themselves likely dating back to the “last glacial maximum,” the most recent of the five ice ages.

Parsons Island isn’t the only “pre-Clovis” site to have been discovered in recent years, but most others have faced their own forms of controversy. Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, for example, was excavated by archaeologist James Adovasio in 1973 and dates back 16,000 years. At the time, however, others in the field cast significant doubt on the find, and it is still heavily criticized today.

Another archaeologist, Tom Dillehay, said part of the issue stems from the “Clovis police,” a group of scientific gatekeepers who seem to reject any pre-Clovis sites, with or without good reason. That only started to change in 1997 with a site in Chile called Monte Verde, when a group of respected archaeologists declared it authentic. Dillehay, however, had begun working at the Monte Verde site decades earlier.

Article Citation:

Harvey, Austin. “Prehistoric Tools Found In Maryland Suggest Humans Came To America 7,000 Years Earlier Than Previously Thought.” May 24, 2024