‘The Dreaming’ in Aboriginal Australia

Home » Articles and News » ‘The Dreaming’ in Aboriginal Australia

by Lynne Hume Ph.D

The term ‘The Dreaming’ is a Western translation of an Aboriginal concept that is difficult for Westerners to understand, and because most of Aboriginal culture is often of a secret-sacred nature, it is not permissible for Aboriginal people to convey much of it to others, particularly non-Aborigines.

The term ‘The Dreaming’ is a Western translation of an Aboriginal concept that is difficult for Westerners to understand, and because most of Aboriginal culture is often of a secret-sacred nature, it is not permissible for Aboriginal people to convey much of it to others, particularly non-Aborigines.

There were many traditional languages throughout Aboriginal Australia prior to contact with Western culture, some of which are no longer spoken, each of which had its own way of referring to what was a pervasive theme. In the following comment, made by Mussolini Harvey, an Aboriginal man from Yanyuwa country, (Gulf of Carpentaria, Australia), he calls the Dreaming ‘Yijan’ because he speaks Yanyuwa. His statement demonstrates both the difficulty of conveying the Law, and how the term ‘Dreaming’ depends on the local indigenous language:

White people ask us all the time, what is Dreaming? This is a hard question because Dreaming is a really big thing for Aboriginal people. In our language, Yanyuwa, we call the Dreaming Yijan. The Dreamings made our Law. This Law is the way we live, our rules. This Law is our ceremonies, our songs, our stories; all of these things came from the Dreaming. One thing that I can tell you though is that our Law is not like European Law which is always changing – new government, new laws; but our Law cannot change, we did not make it. The Law was made by the Dreamings many, many years ago and given to our Ancestors and they gave it to us.

The Dreaming (or Law) then, is integral to Aboriginal culture. It is the link between human beings, land, and everything that inhabits the land. Aboriginal Elder George Tinamin says:

‘One Land, One Law, One People’

Ngangatja apu wiya, ngayuku tjamu –

This is not a rock, it is my grandfather.

This is a place where the dreaming

Comes up, right up from inside the ground.

Everything is interconnected. It is expressed through stories, ceremony, and song cycles, and through Aboriginal art. Each part of the entire triad of land-humans-environment needs to maintain a balance with every other part and this is done through ceremony.

The recounting of myths and their meanings is part of the importance of knowledge as ownership. As a person progresses in age and through the process of initiations, older and fully initiated people reveal more knowledge to them. And there are layers of meaning. Traditional artwork as well, contains levels of meaning according to the knowledge that has been passed to the viewer. Some Law ceremonies and sites pertain to ‘women’s business’; some to ‘men’s business’; others to both genders.

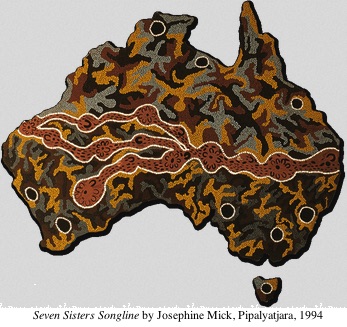

A song or story can follow an actual geographical tract called a ‘songline’, where Aborigines follow the stories that are depicted in a particular Dreaming. The songs may appear to contain a simple statement, but to the enculturated performer, have multiple meanings. The more an individual participates in ceremony, the more deeply he or she learns of the layers of meaning.

A song or story can follow an actual geographical tract called a ‘songline’, where Aborigines follow the stories that are depicted in a particular Dreaming. The songs may appear to contain a simple statement, but to the enculturated performer, have multiple meanings. The more an individual participates in ceremony, the more deeply he or she learns of the layers of meaning.

Very briefly, the ‘Dreaming’ can be said to relate to the idea of an ancestral presence which exists as a spiritual power that is deeply present in the land. This presence (sometimes referred to as ‘power’) also exists in certain paintings, in some dance performances, and in songs, and ceremonial objects. When an Aboriginal person says, ‘this is my Dreaming’, they are referring to a localized area they call ‘my country’, which they ‘belong to’, and to the myths, ceremonies and songs that those stories describe and enact.

Relationships are valued over material wealth, an aspect of Aboriginal culture that has not diminished with the advent of Europeans. The loss of connection to family and the deeply significant emotional and spiritual ties with their country through early government and missionary intervention has changed much of traditional Aboriginal culture, and many who now live in cities, have much less opportunity to participate in traditional ceremonies.

My book, Ancestral Power, published by Melbourne University Press (2002) takes a sweeping look at the ‘Dreaming’, by exploring a wide range of existing literature on Aboriginal cosmology and spiritual practices, together with studies of Aboriginal art, data from anthropologists and ethnomusicologists, and statements by Aboriginal people from many different regional areas of Australia. For readers who want in-depth studies on particular areas and themes, I encourage them to refer to the many sources in the bibliography.

About the Author: Lynne Hume, Ph.D.

About the Author: Lynne Hume, Ph.D.

Lynne, Hume is an Anthropologist, Honorary Research Consultant, and Associate Professor (retired) in Studies in Religion at The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. She has researched and published on Australian indigenous culture, contemporary Paganism, new religious movements, altered states of consciousness, and sensorial anthropology as well as magical experiences and religion and dress.

Her book publications are: The Varieties of Magical Experience co-authored with Dr Nevill Drury) (in press with Praeger ABC-CLIO); The Religious Life of Dress (forthcoming with Berg); Portals: Opening Doorways to Other Realities through the Senses (2007) Oxford and New York: Berg; Ancestral Power: The Dreaming, Consciousness and Aboriginal Australians (2002) Melbourne University Press; Witchcraft and Paganism in Australia (1997) Melbourne University Press; Anthropologists in the Field: Cases in Participant Observation (with Jane Mulcock) (2004) New York: Columbia University Press; Popular Spiritualities: the Politics of Contemporary Enchantment (with Kathleen McPhillips) (2006) Aldershot, England and Burlington, USA: Ashgate. She has also published work in numerous academic journals and several encyclopedias and supervised PhD students through to completion of their doctorates. Hume lives in Australia.

One Book Review:

One Book Review:

Ancestral Power by Lynne Hume is a treatise on Aboriginal magic for post-modern days. The deeds of medicine men and sacred musicians across the continent are probed: the near-hypnotic powers of indigenous paintings and songs are given scientific explanation. “Could the Dreaming have been based, among other things, on the interface between culture, environment and experiences in altered sates of consciousness”?

– The Weekend Australian

Home » Articles and News » ‘The Dreaming’ in Aboriginal Australia